The Mexicanas is a play of double series and double exposures; a play whose board is reminiscent of an old-fashioned, variegated diaporama.

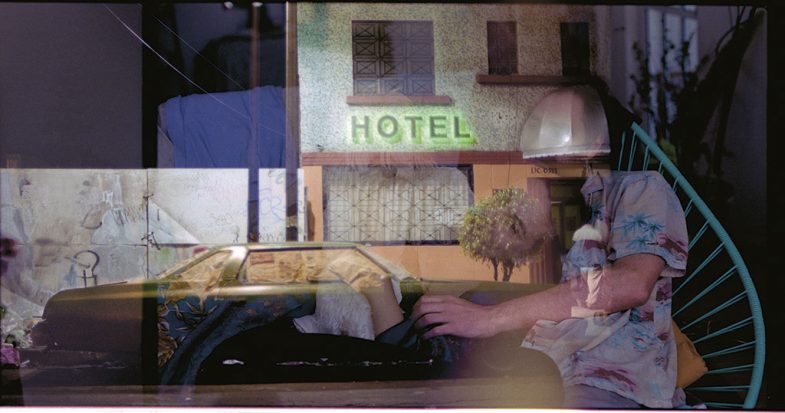

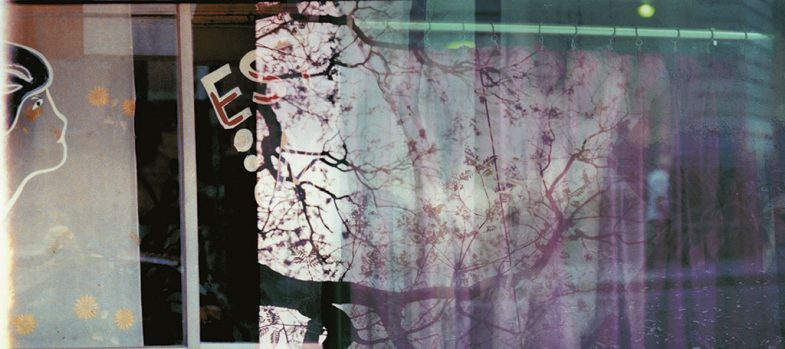

The first of these series, dating back to early 2015, consists of images that seem to come out of a collector’s cupboard for old photographs: lost scenes from travelogues that may have gone through too many hands, too many moves; over-exposed, piled, untied from any specific time or space. Images of Mexico City, as charming in their surface effects—veiled, dyed, perforated, overlapped—as seemingly unwarranted.

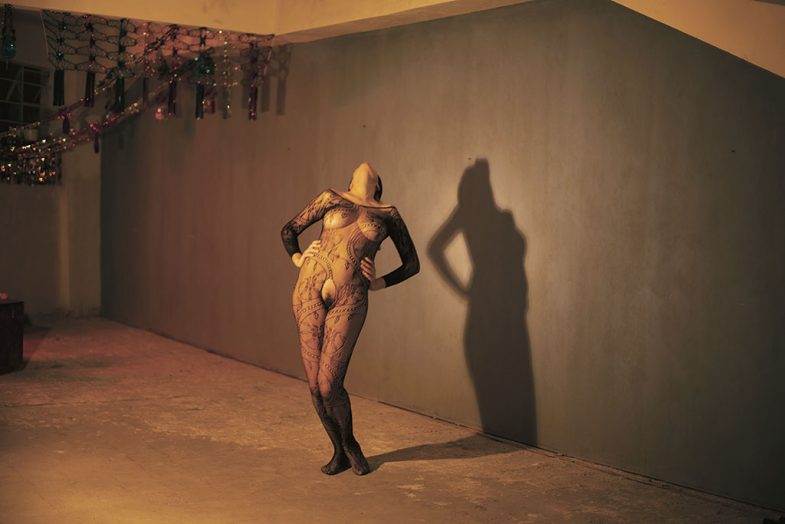

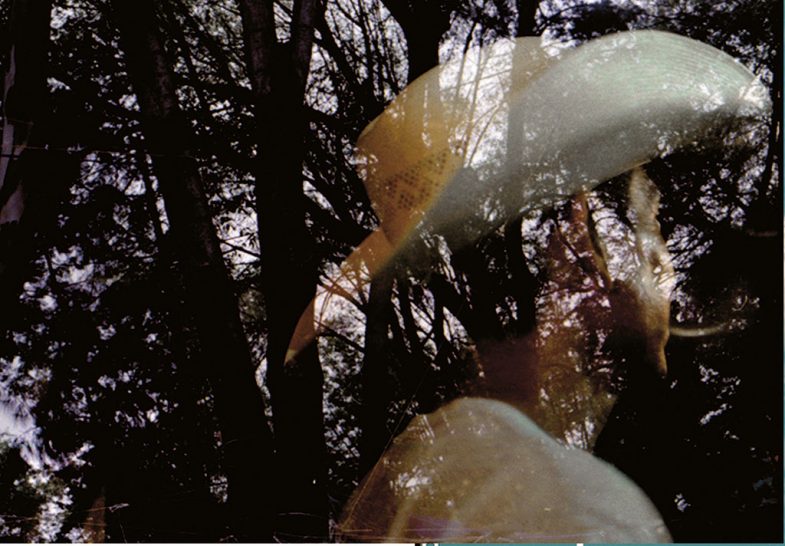

Thus, more than views, these images are above all modest exercises on the obstruction of the gaze: fabrics, velvet foldings, raffia curtains and unfurled canvases interposing one screen after another; branches and trees that may rather be looms or laces; veils that are also crystals, reflections and textures.

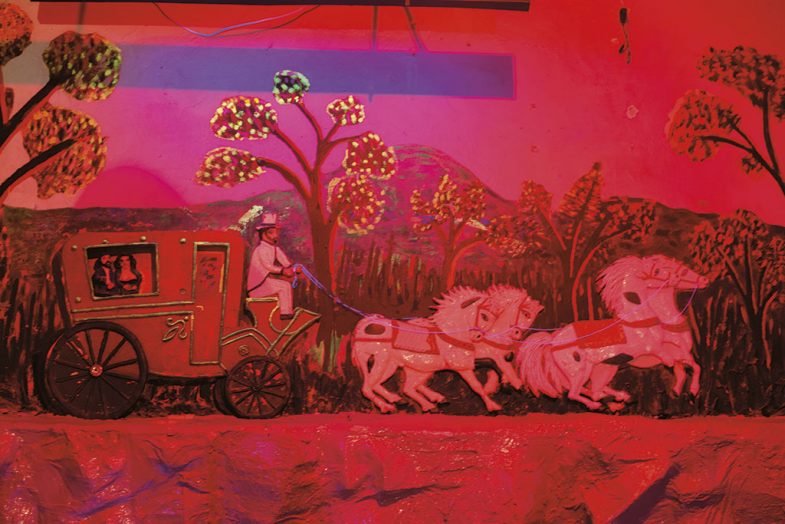

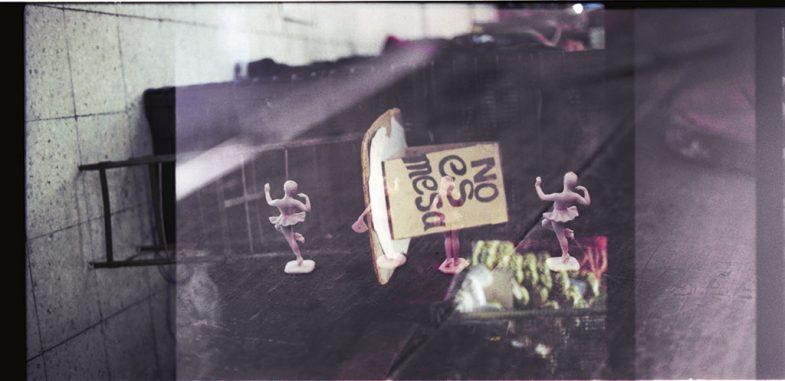

After this parade of gauzes, clichéd images come and go before our eyes to the rhythm of a postcard trolley spinning in a flea market: rusty gringo cars and hotel facades; street cake stands and billboards showing charro characters; deco-style illustrations of refined women and cheap plastic miniature ballerinas; the v-neck of a pachuco shirt, Chinese lamps, double-brimmed straw hats, the long feather of a pheasant.

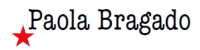

But there is more to it. Also, there are images that seem to be late for a date: closed gates made of iron, raw canvas awnings secured by ropes that may be part of a dismantled urban camp, or a police unit crossed, in the foreground, by a figure on horseback that is just about to disappear. And finally—as an intruder in this series coming to announce the following—we find the headless body of a woman; her hands at the height of her hips, the fold of her skirt yellowished by celluloid chemicals.

As if this world, between the cliche and an extreme opacity, was not hers at all.

An enchanted world, no doubt. But what kind of enchantment is this? Who haunts, and who is haunted by the ghosts that inhabit it? The spectral and overexposed city in these photographs is nothing but the materialization of a white noise over which other images—The Mexicanas—strive to come into view.

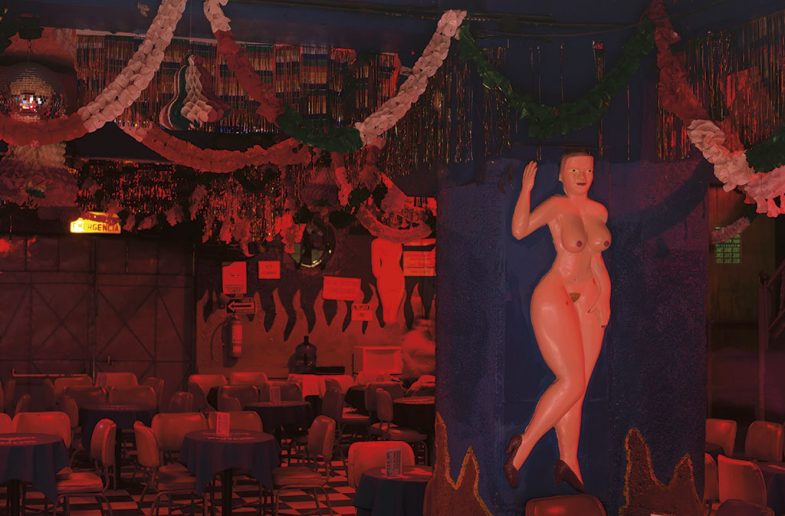

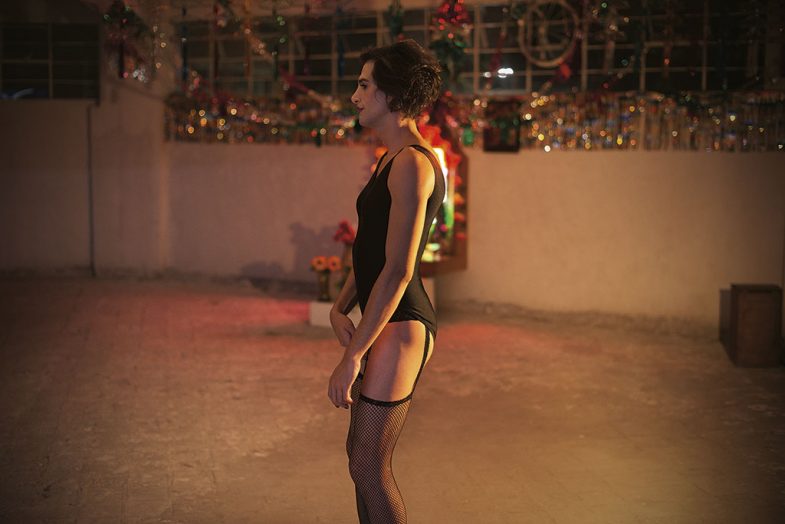

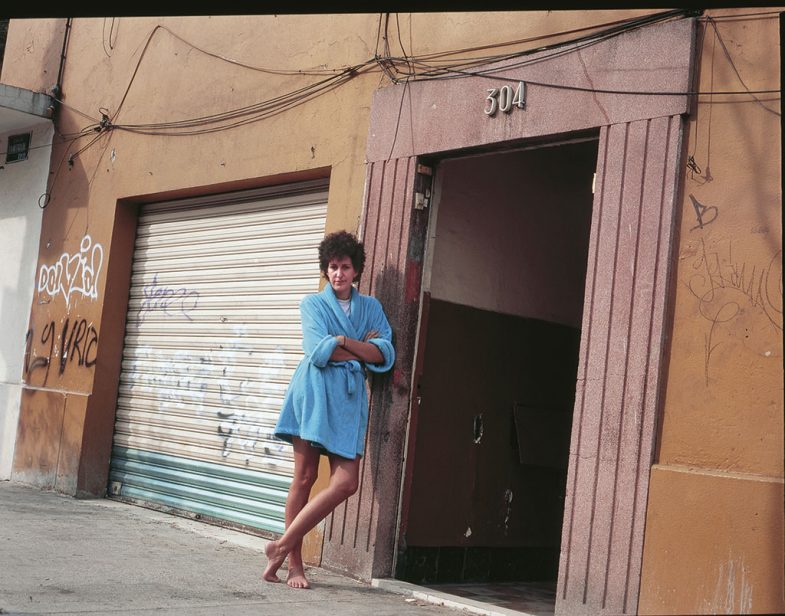

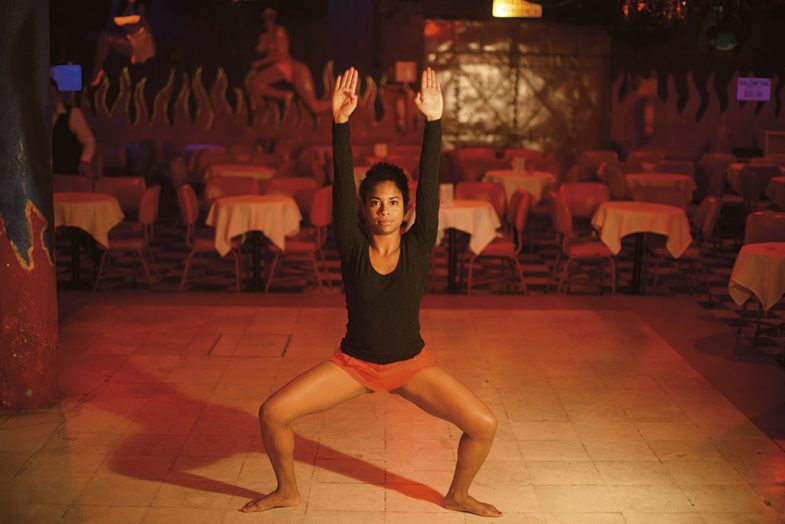

Mexican, but also Spanish, Brazilian, Colombian… the images of these women, overexposed and interspersed in that carousel of worn-out stereotypes, compose a second series and respond to a different working process. These are portraits of women who, in the interior halls of the Barba Azul cabaret in Mexico City—where they work as ficheras—, have lent their image so a gesture, that is no longer their own, may appear: nor the spectacular gesture that stigmatizes them inside the ballroom, nor the documentary gesture that naturalizes them in the closed circuit of their intimate spaces.

On the contrary, these gestures strive to bring out a figure that is rehearsed in the encounter with the camera. They are, as it were, the shapes of a joint effort to give themselves an image. Against the spectral quality that exposes them to disappear, these gestures attest to an effort to appear and invent a common gesture.

Miguel Errazu, “Re-exposure.” This insert accompanies the Paola Bragado’s exhibition catalogue, The Mexicanas (Cuadernos de la Kursala no. 81. Cádiz and Mexico City: Kursala and HydraInframundo, 2021).